sleep aids

-

joemike

sleep aids

diagnosed with OSA ...have been on CPAP for 3 months with some good results and some bad experiences .. the biggest issue is falling asleep takes 3-4 hours a night!!!! What is the best remedy?

Re: sleep aids

What specifically seems to be the problem - just awareness of the mask, mask not fitted properly, you being afraid to move ?

Jumping straight to sleeping pills should not be necessary and won't help long term... lots of other good answers here and you're so not alone in having trouble getting going!

Click on User Ctl Panel under the logo, go to Profile, fill out full name/model of your machine (plse use text, not icons) and mask type, with pressure settings (we're not nosy, but it will help us to help you in future and will always appear under your posts each time, tho' you can edit in future to change settings, etc.). And try to stick to one thread if possible so we don't run around looking for history each time.

Jumping straight to sleeping pills should not be necessary and won't help long term... lots of other good answers here and you're so not alone in having trouble getting going!

Click on User Ctl Panel under the logo, go to Profile, fill out full name/model of your machine (plse use text, not icons) and mask type, with pressure settings (we're not nosy, but it will help us to help you in future and will always appear under your posts each time, tho' you can edit in future to change settings, etc.). And try to stick to one thread if possible so we don't run around looking for history each time.

Re: sleep aids

Assuming that your CPAP is not the issue, then here are some things to check:joemike wrote:diagnosed with OSA ...have been on CPAP for 3 months with some good results and some bad experiences .. the biggest issue is falling asleep takes 3-4 hours a night!!!! What is the best remedy?

1. Cool to cold bedroom (60-65 degrees), or a bed cooler such as a ChiliPad or NuYu Sleep system.

2. No light with the possible exception of a red nightlight. Any blue light is especially bad since blue light is your brain's "wake-up" signal, which stops the production of melatonin. Odd, but many bedroom alarm clocks use blue lighting - bad thing.

3. If you cannot totally eliminate bedroom light, then wear a sleeping mask. However, wearing one may be difficult with your CPAP mask. Also, make sure that it has recessed areas for your eyes (the mask should not make direct connect with your mask). I wear one with my "pillow" mask.

4. Limit the use of all lighted devices a few hours before bedtime (such as computers, TVs, tablets, etc.). These devices will delay your body's start of creating melatonin. If you are using a computer late into the evening, there is a free program that will automatically remove the blue portion of the light spectrum being displayed on your computer's screen.

5. Get out into the sunshine the first thing in the morning.

6. A "pink' noise generator may be helpful in that it covers-up random sounds. If you have a "smartphone" or other smart device, there are many free noise Apps available. Then it only requires the purchase of a cheap speaker and you are set to go. A Bluetooth speaker setup is very handy.

I hope that some of these ideas help.

Machine: ResMed AirSense 11 w/Humidifier

Mask Make & Model: Pillow mask

CPAP Pressure: 9.4

CPAP Reporting Software: OSCAR & SleepHQ

Mask Make & Model: Pillow mask

CPAP Pressure: 9.4

CPAP Reporting Software: OSCAR & SleepHQ

-

joemike

Re: sleep aids

melatonin was suggested in a post today for a similar problem that I am experiencing(taking a long time to fall asleep) Is this advice I could follow without consulting my Dr?

Re: sleep aids

You're free to do whatever you want, but you didn't address what I said or suggested... and we'd like to help the source problem, not just give you (a stranger here) a sleeping pill (that's known to backfire within a short time for lots of people).

Re: sleep aids

joemike,joemike wrote:melatonin was suggested in a post today for a similar problem that I am experiencing(taking a long time to fall asleep) Is this advice I could follow without consulting my Dr?

I strongly suggest you follow Julie's advice before resorting to sleep aids which I am not against by the way. But using them without making sure your therapy is optimized would be like putting a bandaid on a cut that needs stitches.

49er

_________________

| Mask: SleepWeaver Elan™ Soft Cloth Nasal CPAP Mask - Starter Kit |

| Humidifier: S9™ Series H5i™ Heated Humidifier with Climate Control |

| Additional Comments: Use SleepyHead |

Re: sleep aids

joe, Taking sleep medication while CPAPing.

I take 5 mg of Zolpidem (generic Ambien, not the extended release), and fall asleep within 15 min. If I don't fall asleep within 30 minutes I take another 5 mg. Rarely, it happens that I need to take 5 mg more but I don't take this dose if I have less than 6 hours left to sleep. I usually sleep for about 6 1/2 hours.

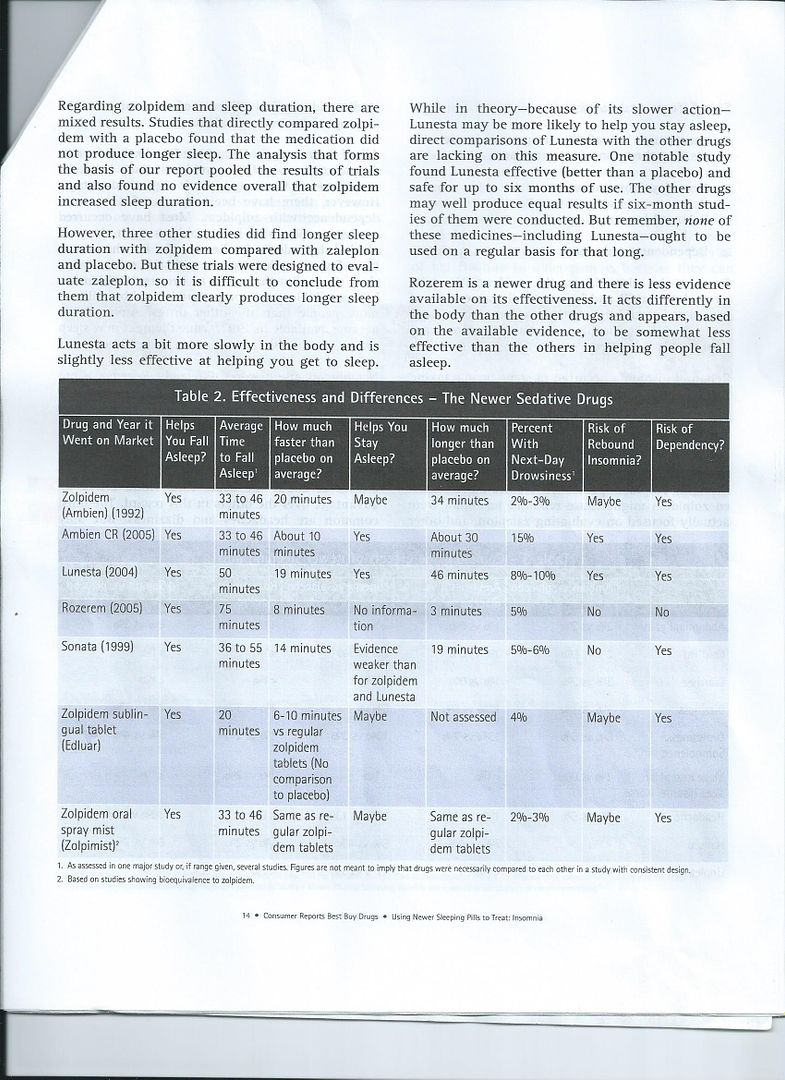

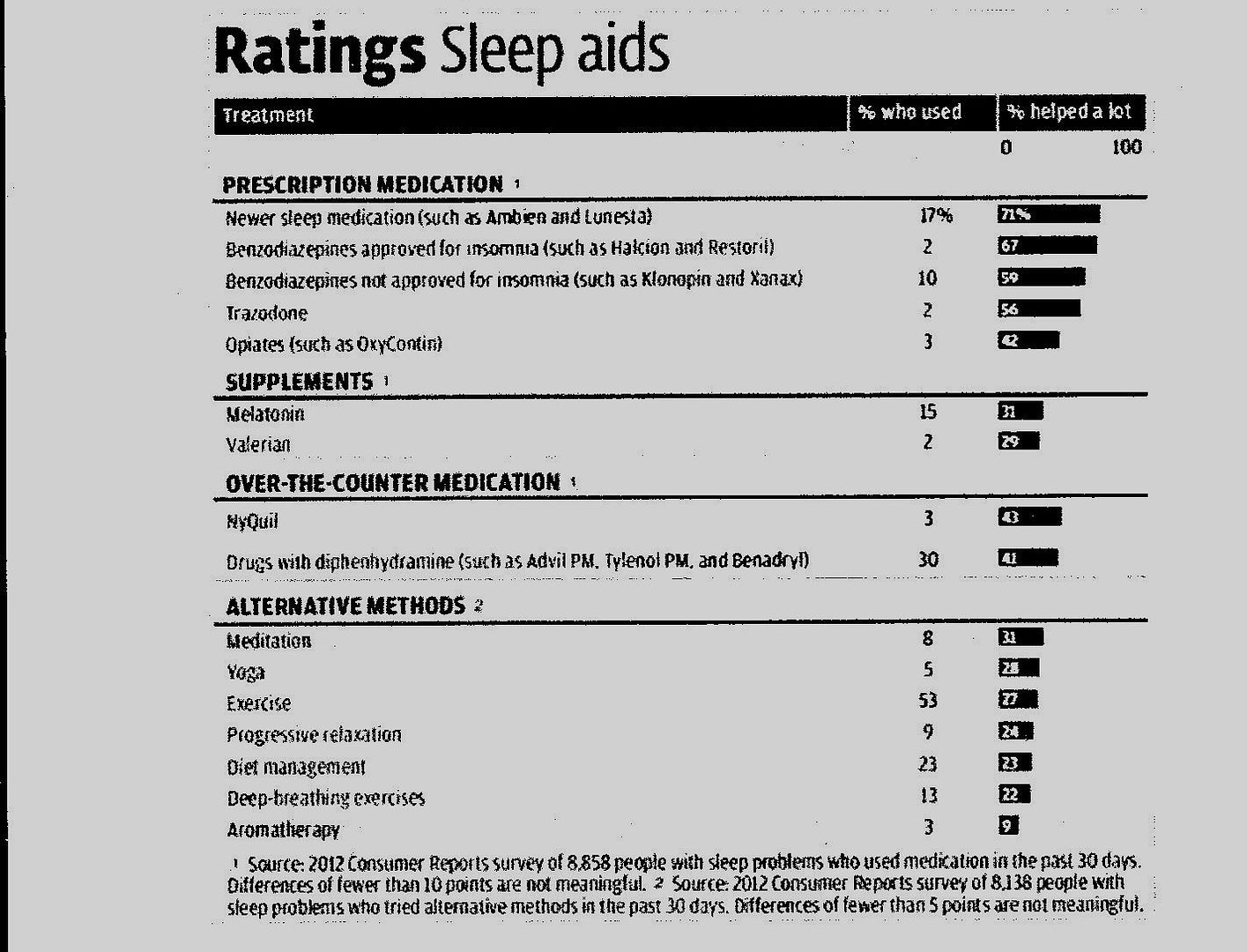

In 2012 Consumer Reports on Health had a survey of nearly 9000 people with problems falling asleep. Here is a result of this survey:

If you are Insomniac then sleep medications might not work according to this report:

A 77-year-old overweight woman with hypertension and arthritis reports that she has had trouble sleeping for “as long as I can remember.” She has taken hypnotic medications nightly for almost 50 years; her medication was recently switched from lorazepam (1 mg), which had been successful, to trazodone (25 mg) by her primary care physician, who was concerned about her use of the former. She spends 9 hours in bed, from 11 p.m. to 8 a.m. She has only occasional difficulty falling asleep, but she awakens two to three times per night to urinate and lies in bed for over an hour at those times, “just worrying.” How should her case be managed?

The Clinical Problem

Dissatisfaction with sleep owing to difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep or to waking up too early is present in roughly one third of adults on a weekly basis.1 For most, such sleep difficulties are transient or of minor importance. However, prolonged sleeplessness is often associated with substantial distress, impairment in daytime functioning, or both. In such cases, a diagnosis of insomnia disorder is appropriate. Reductions in perceived health2 and quality of life,3 increases in workplace injuries and absenteeism,4 and even fatal injuries5 are all associated with chronic insomnia. Insomnia symptoms may also be an independent risk factor for suicide attempts and deaths from suicide, independent of depression.6 Neuropsychological testing reveals deficits in complex cognitive processes, including working memory and attention switching,7 which are not simply related to impaired alertness.

Key Clinical Points

Insomnia Disorder

•

Prolonged insomnia is associated with an increased risk of new-onset major depression and may be an independent risk factor for heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes, especially when combined with sleep times of less than 6 hours per night.

•

Evaluation of a patient with insomnia should include a complete medical and psychiatric history and a detailed assessment of sleep-related behaviors and symptoms.

•

Cognitive behavioral therapy, which includes setting realistic goals for sleep, limiting time spent in bed, addressing maladaptive beliefs about sleeplessness, and practicing relaxation techniques, is the first-line therapy for insomnia.

•

In those with acute insomnia due to a defined precipitant, use of Food and Drug Administration–approved hypnotic medications is indicated.

•

Long-term use of benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, low-dose antidepressants, melatonin agonists, or an orexin antagonist should be considered for patients with severe insomnia that is unresponsive to other approaches.

Older diagnostic systems attempted to distinguish “primary” from “secondary” insomnia on the basis of the inferred original cause of the sleeplessness. However, because causal relationships between different medical and psychiatric disorders and insomnia are often bidirectional, such conclusions are unreliable. In addition, owing to the poor reliability of insomnia subtyping8 based on phenotype or pathophysiology, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders9 takes a purely descriptive approach that is based on the frequency and duration of symptoms (Table 1Table 1

Criteria for the Diagnosis of Insomnia Disorder.

), allowing a diagnosis of insomnia disorder independent of, and in addition to, any coexisting psychiatric or medical disorders. The clinician should monitor whether treatment of such coexisting disorders normalizes sleep, and if not, treat the insomnia disorder independently.

Coexisting Conditions

Insomnia is more common in women than in men, and its prevalence is increased in persons who work irregular shifts and in persons with disabilities.2 Although the elderly are more likely than younger people to report insomnia symptoms, actual insomnia diagnoses are not more frequent in the elderly, because the effects of sleeplessness on daytime functioning appear to be less dramatic. Roughly 50% of those with insomnia have a psychiatric disorder,10 most commonly a mood disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder) or an anxiety disorder (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder). Various medical illnesses are also associated with insomnia, particularly those that cause shortness of breath, pain, nocturia, gastrointestinal disturbance, or limitations in mobility.11

Although roughly 80% of those with major depressive disorder have insomnia, in nearly one half of those cases, the insomnia predated the onset of the mood disorder.12 A meta-analysis of more than 20 studies concluded that persistent insomnia is associated with a doubling of the risk of incident major depression.13 Associations have also been reported between insomnia and increased risks of acute myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease,14 heart failure,15 hypertension,16 diabetes,17 and death,18 particularly when insomnia is accompanied by short total sleep duration (<6 hours per night).19

Prevalence and Natural History

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder, with a reported prevalence of 10 to 15%, depending on the diagnostic criteria used.1,2 Insomnia symptoms commonly wax and wane over time, though roughly 50% of those with more severe symptoms who meet criteria for insomnia disorder have a chronic course.20 The 1-year incidence of insomnia is approximately 5%. Difficulty maintaining sleep is the most common symptom (affecting 61% of persons with insomnia), followed by early-morning awakening (52%) and difficulty falling asleep (38%); nearly half of those with insomnia have two or more of these symptoms.11 Manifestations of insomnia often change over time; for example, a person may initially have difficulty falling asleep but subsequently have difficulty staying asleep, or vice versa.

Pathophysiology

Insomnia is commonly conceptualized as a disorder of nocturnal and daytime hyperarousal, which is both a consequence and a cause of insomnia and is expressed at cognitive and emotional as well as physiological levels.21 People with insomnia often describe excessive worry, racing thoughts, and selective attention to arousing stimuli. Hyperarousal is manifested physiologically in those with insomnia as an increased whole-body metabolic rate, elevations in cortisol level, increased whole-brain glucose consumption during both the waking and the sleeping states, and increased blood pressure and high-frequency electroencephalographic activity during sleep.21

Strategies and Evidence

Evaluation

The evaluation of insomnia requires assessment of nocturnal and daytime sleep-related symptoms, their duration, and their temporal association with psychological or physiological stressors. Because there are many pathways to insomnia, a full evaluation includes a complete medical and psychiatric history as well as assessment for the presence of specific sleep disorders (e.g., sleep apnea or the restless legs syndrome). Questioning the patient regarding thoughts and behaviors in the hours before bedtime, while in bed attempting to sleep, and at any nocturnal awakenings may provide insight into processes interfering with sleep. A daily sleep diary documenting bedtime, any awakenings during the night, and final wake time over a period of 2 to 4 weeks can identify excessive time in bed and irregular, phase-delayed, or phase-advanced sleep patterns.

There is often a mismatch between self-reported and polysomnographically recorded sleep in those with insomnia, in which the self-reported time to fall sleep is overestimated and total sleep time is underestimated.22 Because polysomnography cannot distinguish those with insomnia from those without it,23 the diagnosis of insomnia is made clinically. Polysomnography is not indicated in the evaluation of insomnia unless sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, or an injurious parasomnia (e.g., rapid-eye-movement [REM] sleep behavior disorder) is suspected or unless usual treatment approaches fail.

Management

The choice of treatment of insomnia depends on the specific insomnia symptoms, their severity and expected duration, coexisting disorders, the willingness of the patient to engage in behavioral therapies, and the vulnerability of the patient to the adverse effects of medications. Patients with an acute onset of insomnia of short duration often have an identifiable precipitant (e.g., a medical illness or the loss of a loved one). In such cases, Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved pharmacologic agents (discussed below) are recommended for short-term use. In patients with chronic insomnia, appropriate treatment of coexisting medical, psychiatric, and sleep disorders that contribute to insomnia is essential for improving sleep. Nevertheless, insomnia is often persistent even with proper treatment of these coexisting disorders.24

Treatment for chronic insomnia includes two complementary approaches: cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacologic treatments.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT addresses dysfunctional behaviors and beliefs about sleep that contribute to the perpetuation of insomnia (Table 2Table 2

Components of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia.

), and it is considered the first-line therapy for all patients with insomnia,25 including those with coexisting conditions.26 CBT is traditionally delivered in either individual or group settings over six to eight meetings. In a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials involving persons with insomnia without coexisting conditions, CBT had significant effects on time to sleep onset (mean difference [CBT group minus control group], −19 minutes) and time awake after sleep onset (mean difference, −26 minutes), though benefits with regard to total sleep time were small (mean difference, 8 minutes), a finding consistent with the restrictions on overall time spent in bed.27 The benefits were generally maintained in studies lasting 6 to 12 months. In short-term, randomized trials comparing behavioral treatments with benzodiazepine-receptor agonists (discussed below) in persons with insomnia without coexisting conditions, CBT had less immediate efficacy, but the intervention groups did not differ significantly in time to sleep onset or total sleep time at 4 to 8 weeks,28 and CBT was superior when assessed 6 to 12 months after treatment discontinuation.29 A barrier to the implementation of CBT is the lack of providers with expertise in its delivery. This limitation has begun to be addressed by the use of shorter therapies30 and Internet-based CBT,31 which have shown efficacy similar to that of longer and face-to-face delivery of CBT. However, sleep hygiene alone (Table 2), which is commonly recommended as an initial approach for insomnia, is not an effective treatment for insomnia.32

Adherence to CBT is less than optimal in clinical practice,33 probably as a result of the extensive behavioral changes required (e.g., reducing time spent in bed and getting out of bed when awake), the delay in efficacy (during which there are often short-term reductions in total sleep time),34 and pessimism that such approaches can be effective.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Several medications, with differing mechanisms of action, are used to treat insomnia, reflecting the multiple neural systems that regulate sleep (Table 3Table 3

Medications Commonly Used for Insomnia.

). Roughly 20% of U.S. adults use a medication for insomnia in a given month,35 and many others use alcohol for this purpose. Nearly 60% of medication use is with nonprescription sleep aids, primarily antihistamines. In the few existing placebo-controlled trials, however, diphenhydramine had at best modest benefit for either mild intermittent insomnia36 or insomnia in the elderly37 and caused daytime sedation and anticholinergic side effects (e.g., constipation and dry mouth) that are particularly problematic in older persons.

Benzodiazepine-Receptor Agonists

Benzodiazepine-receptor agonists include agents with a benzodiazepine chemical structure and “nonbenzodiazepines” without this structure. There is little convincing evidence from comparative trials that these two subtypes differ from each other in clinical efficacy or side effects. Because benzodiazepine-receptor agonists vary predominantly in their half-life, the specific choice of drug from this class is usually based on the insomnia symptom (e.g., difficulty initiating sleep vs. difficulty maintaining sleep). FDA approval of these medications is for bedtime use, with the exception of specifically formulated sublingual zolpidem (1.75 mg for women and 3.5 mg for men). Although not FDA-approved or rigorously studied for middle-of-the-night use, short-acting agents (e.g., zolpidem at a dose of 2.5 mg, and zaleplon at a dose of 5 mg) can also be used effectively to promote a return to sleep as long as 4 hours remain before the user plans to get up in the morning. The use of very-long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., clonazepam, which has a half-life of 40 hours) for uncomplicated insomnia (i.e., in the absence of a daytime anxiety disorder) is not recommended owing to the risk of daytime side effects.

In a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled polysomnographic trials involving patients with chronic insomnia without coexisting conditions, benzodiazepine-receptor agonists showed significant effects on time to sleep onset (mean difference [group receiving benzodiazepine-receptor agonist minus control group], −22 minutes), time awake after sleep onset (mean difference, −13 minutes), and total sleep time (mean difference, 22 minutes).38 In placebo-controlled trials, persistent self-reported efficacy for insomnia was shown for nightly use of eszopiclone for 6 months39 and for intermittent use of extended-release zolpidem over a period of 6 months.40 A randomized, controlled trial involving patients with chronic insomnia showed that as compared with CBT alone, the combination of CBT and a benzodiazepine-receptor agonist was associated with a larger increase in total sleep time at 6 weeks as well as a higher remission rate at 6 months.29

Benzodiazepine-receptor agonists have a number of potential acute adverse effects, including daytime sedation, delirium, ataxia, anterograde memory disturbance, and complex sleep-related behaviors (e.g., sleepwalking and sleep-related eating, which are most common with the short-acting agents). As a result, they have been associated with an increase in motor-vehicle accidents41 and, in the elderly, falls (albeit inconsistently)42 and fractures. Recent longitudinal research suggests an association of long-term use of benzodiazepines with Alzheimer’s disease,43 but interpretation of these results is complicated by the possibility of confounding by indication, because anxiety and insomnia may be early manifestations of this disorder. Abuse of these agents is uncommon among persons with insomnia,44 but they should not be prescribed to persons with a history of substance or alcohol dependence or abuse.

Regular reassessment of the benefits and risks of benzodiazepine-receptor agonists is recommended. If discontinuation is indicated, gradual, supervised tapering (e.g., by 25% of the original dose every 2 weeks), in combination with CBT for insomnia, is strongly recommended for chronic users. Roughly one third of patients who used these discontinuation methods had resumed benzodiazepine use by 2 years of follow-up.45

Sedating Antidepressants

The use of sedating antidepressants to treat insomnia takes advantage of the antihistaminergic, anticholinergic, and serotonergic and adrenergic antagonistic activity of these agents. At the low doses commonly used for insomnia, most have little antidepressant or anxiolytic effect. Although data from controlled trials to support its use in insomnia are limited, trazodone is used as a hypnotic agent by roughly 1% of U.S. adults,35 generally at doses of 25 to 100 mg. Its side effects include morning sedation, orthostatic hypotension (at higher doses), and (in rare cases) priapism. Doxepin, a tricyclic antidepressant, is FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia at doses of 3 to 6 mg. It has shown significant effects on sleep maintenance (time awake after sleep onset and total sleep time) but no significant benefit for sleep-onset latency beyond 2 days of treatment.46 Few side effects were observed at these doses. Mirtazapine has antidepressant and anxiolytic efficacy at doses used for insomnia and is a reasonable first option if patients have insomnia coexisting with those disorders, but it may cause substantial weight gain.

Other Agents

The orexin antagonist suvorexant, which was approved by the FDA in 2014 for the treatment of insomnia, showed decreased time to sleep onset, decreased time awake after sleep onset, and increased total sleep time in short-term randomized trials.47 At higher doses (30 to 40 mg, which were not approved by the FDA owing to a 10% rate of daytime sedation), suvorexant showed persistent efficacy for these measures after 1 year of nightly use48; lower doses have not been studied for more than 12 weeks. Its major side effect at lower doses is morning sleepiness (5% of patients).

Ramelteon is a melatonin-receptor agonist that is FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia. Short-term studies as well as a controlled 6-month trial showed small-to-moderate benefits for time to sleep onset but no significant improvement in total sleep time or time awake after sleep onset.49 Side effects were limited to rare next-day sedation. A meta-analysis of trials of melatonin for insomnia (at a wide range of doses and in immediate-release and controlled-release forms) showed small benefits for time to sleep onset and total sleep time.50 However, the quality control of over-the-counter melatonin products is unclear.

Although controlled clinical trials to support its use are lacking, gabapentin is occasionally used for insomnia, predominantly in patients who have had an inadequate response to other agents, who have a contraindication to benzodiazepine-receptor agonists (e.g., a history of drug or alcohol abuse), or who have neuropathic pain or the restless legs syndrome. Potential side effects include daytime sedation, weight gain, and dizziness.

Areas of Uncertainty

Insomnia is an independent risk factor for depression, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. Controlled studies are needed to determine whether long-term treatment of insomnia with CBT or medications (or both) can reduce the risk of these disorders.

Both sleeplessness and the pharmacologic therapies used to treat insomnia are associated with complications. In those who do not choose CBT or do not have a response to it, long-term randomized trials comparing benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, sedating antidepressants, and the orexin antagonist suvorexant to inform the choice of medications are lacking.

Guidelines

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine25 and the National Institutes of Health51 have published guidelines for the diagnosis and management of insomnia. The recommendations in this article are generally consistent with those guidelines.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The woman in the vignette has a long history of insomnia, now complicated by nocturia and pain. Recently, owing to her physician’s concerns about her benzodiazepine use, she was switched to a low dose of trazodone, but she reports frequent and prolonged awakenings. Attempting to discontinue lorazepam and replacing it with trazodone were reasonable, given the amnestic and psychomotor side effects of benzodiazepines, although data from studies that directly compare these agents are limited. I would strongly recommend a trial of CBT, including (but not limited to) educating her that 7 hours is an adequate amount of sleep, reducing the time from bedtime to final awakening to that amount, and advising her to get in bed only when sleepy and to get out of bed when not sleeping. Over time, these approaches should reduce the duration of nocturnal awakenings, although she should be cautioned initially about an increase in daytime sleepiness. Attention to her nocturia and nocturnal pain will further minimize her nocturnal awakenings and their duration. If these approaches are ineffective, I would consider an increase in the trazodone dose (if this does not cause unacceptable side effects) or a return to lorazepam, informing her of (and regularly reassessing) benefits and potential risks."

Source: John W. Winkelman, M.D., Ph.D. in NEJM from 2 months ago

I take 5 mg of Zolpidem (generic Ambien, not the extended release), and fall asleep within 15 min. If I don't fall asleep within 30 minutes I take another 5 mg. Rarely, it happens that I need to take 5 mg more but I don't take this dose if I have less than 6 hours left to sleep. I usually sleep for about 6 1/2 hours.

In 2012 Consumer Reports on Health had a survey of nearly 9000 people with problems falling asleep. Here is a result of this survey:

If you are Insomniac then sleep medications might not work according to this report:

A 77-year-old overweight woman with hypertension and arthritis reports that she has had trouble sleeping for “as long as I can remember.” She has taken hypnotic medications nightly for almost 50 years; her medication was recently switched from lorazepam (1 mg), which had been successful, to trazodone (25 mg) by her primary care physician, who was concerned about her use of the former. She spends 9 hours in bed, from 11 p.m. to 8 a.m. She has only occasional difficulty falling asleep, but she awakens two to three times per night to urinate and lies in bed for over an hour at those times, “just worrying.” How should her case be managed?

The Clinical Problem

Dissatisfaction with sleep owing to difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep or to waking up too early is present in roughly one third of adults on a weekly basis.1 For most, such sleep difficulties are transient or of minor importance. However, prolonged sleeplessness is often associated with substantial distress, impairment in daytime functioning, or both. In such cases, a diagnosis of insomnia disorder is appropriate. Reductions in perceived health2 and quality of life,3 increases in workplace injuries and absenteeism,4 and even fatal injuries5 are all associated with chronic insomnia. Insomnia symptoms may also be an independent risk factor for suicide attempts and deaths from suicide, independent of depression.6 Neuropsychological testing reveals deficits in complex cognitive processes, including working memory and attention switching,7 which are not simply related to impaired alertness.

Key Clinical Points

Insomnia Disorder

•

Prolonged insomnia is associated with an increased risk of new-onset major depression and may be an independent risk factor for heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes, especially when combined with sleep times of less than 6 hours per night.

•

Evaluation of a patient with insomnia should include a complete medical and psychiatric history and a detailed assessment of sleep-related behaviors and symptoms.

•

Cognitive behavioral therapy, which includes setting realistic goals for sleep, limiting time spent in bed, addressing maladaptive beliefs about sleeplessness, and practicing relaxation techniques, is the first-line therapy for insomnia.

•

In those with acute insomnia due to a defined precipitant, use of Food and Drug Administration–approved hypnotic medications is indicated.

•

Long-term use of benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, low-dose antidepressants, melatonin agonists, or an orexin antagonist should be considered for patients with severe insomnia that is unresponsive to other approaches.

Older diagnostic systems attempted to distinguish “primary” from “secondary” insomnia on the basis of the inferred original cause of the sleeplessness. However, because causal relationships between different medical and psychiatric disorders and insomnia are often bidirectional, such conclusions are unreliable. In addition, owing to the poor reliability of insomnia subtyping8 based on phenotype or pathophysiology, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders9 takes a purely descriptive approach that is based on the frequency and duration of symptoms (Table 1Table 1

Criteria for the Diagnosis of Insomnia Disorder.

), allowing a diagnosis of insomnia disorder independent of, and in addition to, any coexisting psychiatric or medical disorders. The clinician should monitor whether treatment of such coexisting disorders normalizes sleep, and if not, treat the insomnia disorder independently.

Coexisting Conditions

Insomnia is more common in women than in men, and its prevalence is increased in persons who work irregular shifts and in persons with disabilities.2 Although the elderly are more likely than younger people to report insomnia symptoms, actual insomnia diagnoses are not more frequent in the elderly, because the effects of sleeplessness on daytime functioning appear to be less dramatic. Roughly 50% of those with insomnia have a psychiatric disorder,10 most commonly a mood disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder) or an anxiety disorder (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder). Various medical illnesses are also associated with insomnia, particularly those that cause shortness of breath, pain, nocturia, gastrointestinal disturbance, or limitations in mobility.11

Although roughly 80% of those with major depressive disorder have insomnia, in nearly one half of those cases, the insomnia predated the onset of the mood disorder.12 A meta-analysis of more than 20 studies concluded that persistent insomnia is associated with a doubling of the risk of incident major depression.13 Associations have also been reported between insomnia and increased risks of acute myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease,14 heart failure,15 hypertension,16 diabetes,17 and death,18 particularly when insomnia is accompanied by short total sleep duration (<6 hours per night).19

Prevalence and Natural History

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder, with a reported prevalence of 10 to 15%, depending on the diagnostic criteria used.1,2 Insomnia symptoms commonly wax and wane over time, though roughly 50% of those with more severe symptoms who meet criteria for insomnia disorder have a chronic course.20 The 1-year incidence of insomnia is approximately 5%. Difficulty maintaining sleep is the most common symptom (affecting 61% of persons with insomnia), followed by early-morning awakening (52%) and difficulty falling asleep (38%); nearly half of those with insomnia have two or more of these symptoms.11 Manifestations of insomnia often change over time; for example, a person may initially have difficulty falling asleep but subsequently have difficulty staying asleep, or vice versa.

Pathophysiology

Insomnia is commonly conceptualized as a disorder of nocturnal and daytime hyperarousal, which is both a consequence and a cause of insomnia and is expressed at cognitive and emotional as well as physiological levels.21 People with insomnia often describe excessive worry, racing thoughts, and selective attention to arousing stimuli. Hyperarousal is manifested physiologically in those with insomnia as an increased whole-body metabolic rate, elevations in cortisol level, increased whole-brain glucose consumption during both the waking and the sleeping states, and increased blood pressure and high-frequency electroencephalographic activity during sleep.21

Strategies and Evidence

Evaluation

The evaluation of insomnia requires assessment of nocturnal and daytime sleep-related symptoms, their duration, and their temporal association with psychological or physiological stressors. Because there are many pathways to insomnia, a full evaluation includes a complete medical and psychiatric history as well as assessment for the presence of specific sleep disorders (e.g., sleep apnea or the restless legs syndrome). Questioning the patient regarding thoughts and behaviors in the hours before bedtime, while in bed attempting to sleep, and at any nocturnal awakenings may provide insight into processes interfering with sleep. A daily sleep diary documenting bedtime, any awakenings during the night, and final wake time over a period of 2 to 4 weeks can identify excessive time in bed and irregular, phase-delayed, or phase-advanced sleep patterns.

There is often a mismatch between self-reported and polysomnographically recorded sleep in those with insomnia, in which the self-reported time to fall sleep is overestimated and total sleep time is underestimated.22 Because polysomnography cannot distinguish those with insomnia from those without it,23 the diagnosis of insomnia is made clinically. Polysomnography is not indicated in the evaluation of insomnia unless sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, or an injurious parasomnia (e.g., rapid-eye-movement [REM] sleep behavior disorder) is suspected or unless usual treatment approaches fail.

Management

The choice of treatment of insomnia depends on the specific insomnia symptoms, their severity and expected duration, coexisting disorders, the willingness of the patient to engage in behavioral therapies, and the vulnerability of the patient to the adverse effects of medications. Patients with an acute onset of insomnia of short duration often have an identifiable precipitant (e.g., a medical illness or the loss of a loved one). In such cases, Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved pharmacologic agents (discussed below) are recommended for short-term use. In patients with chronic insomnia, appropriate treatment of coexisting medical, psychiatric, and sleep disorders that contribute to insomnia is essential for improving sleep. Nevertheless, insomnia is often persistent even with proper treatment of these coexisting disorders.24

Treatment for chronic insomnia includes two complementary approaches: cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacologic treatments.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT addresses dysfunctional behaviors and beliefs about sleep that contribute to the perpetuation of insomnia (Table 2Table 2

Components of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia.

), and it is considered the first-line therapy for all patients with insomnia,25 including those with coexisting conditions.26 CBT is traditionally delivered in either individual or group settings over six to eight meetings. In a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials involving persons with insomnia without coexisting conditions, CBT had significant effects on time to sleep onset (mean difference [CBT group minus control group], −19 minutes) and time awake after sleep onset (mean difference, −26 minutes), though benefits with regard to total sleep time were small (mean difference, 8 minutes), a finding consistent with the restrictions on overall time spent in bed.27 The benefits were generally maintained in studies lasting 6 to 12 months. In short-term, randomized trials comparing behavioral treatments with benzodiazepine-receptor agonists (discussed below) in persons with insomnia without coexisting conditions, CBT had less immediate efficacy, but the intervention groups did not differ significantly in time to sleep onset or total sleep time at 4 to 8 weeks,28 and CBT was superior when assessed 6 to 12 months after treatment discontinuation.29 A barrier to the implementation of CBT is the lack of providers with expertise in its delivery. This limitation has begun to be addressed by the use of shorter therapies30 and Internet-based CBT,31 which have shown efficacy similar to that of longer and face-to-face delivery of CBT. However, sleep hygiene alone (Table 2), which is commonly recommended as an initial approach for insomnia, is not an effective treatment for insomnia.32

Adherence to CBT is less than optimal in clinical practice,33 probably as a result of the extensive behavioral changes required (e.g., reducing time spent in bed and getting out of bed when awake), the delay in efficacy (during which there are often short-term reductions in total sleep time),34 and pessimism that such approaches can be effective.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Several medications, with differing mechanisms of action, are used to treat insomnia, reflecting the multiple neural systems that regulate sleep (Table 3Table 3

Medications Commonly Used for Insomnia.

). Roughly 20% of U.S. adults use a medication for insomnia in a given month,35 and many others use alcohol for this purpose. Nearly 60% of medication use is with nonprescription sleep aids, primarily antihistamines. In the few existing placebo-controlled trials, however, diphenhydramine had at best modest benefit for either mild intermittent insomnia36 or insomnia in the elderly37 and caused daytime sedation and anticholinergic side effects (e.g., constipation and dry mouth) that are particularly problematic in older persons.

Benzodiazepine-Receptor Agonists

Benzodiazepine-receptor agonists include agents with a benzodiazepine chemical structure and “nonbenzodiazepines” without this structure. There is little convincing evidence from comparative trials that these two subtypes differ from each other in clinical efficacy or side effects. Because benzodiazepine-receptor agonists vary predominantly in their half-life, the specific choice of drug from this class is usually based on the insomnia symptom (e.g., difficulty initiating sleep vs. difficulty maintaining sleep). FDA approval of these medications is for bedtime use, with the exception of specifically formulated sublingual zolpidem (1.75 mg for women and 3.5 mg for men). Although not FDA-approved or rigorously studied for middle-of-the-night use, short-acting agents (e.g., zolpidem at a dose of 2.5 mg, and zaleplon at a dose of 5 mg) can also be used effectively to promote a return to sleep as long as 4 hours remain before the user plans to get up in the morning. The use of very-long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., clonazepam, which has a half-life of 40 hours) for uncomplicated insomnia (i.e., in the absence of a daytime anxiety disorder) is not recommended owing to the risk of daytime side effects.

In a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled polysomnographic trials involving patients with chronic insomnia without coexisting conditions, benzodiazepine-receptor agonists showed significant effects on time to sleep onset (mean difference [group receiving benzodiazepine-receptor agonist minus control group], −22 minutes), time awake after sleep onset (mean difference, −13 minutes), and total sleep time (mean difference, 22 minutes).38 In placebo-controlled trials, persistent self-reported efficacy for insomnia was shown for nightly use of eszopiclone for 6 months39 and for intermittent use of extended-release zolpidem over a period of 6 months.40 A randomized, controlled trial involving patients with chronic insomnia showed that as compared with CBT alone, the combination of CBT and a benzodiazepine-receptor agonist was associated with a larger increase in total sleep time at 6 weeks as well as a higher remission rate at 6 months.29

Benzodiazepine-receptor agonists have a number of potential acute adverse effects, including daytime sedation, delirium, ataxia, anterograde memory disturbance, and complex sleep-related behaviors (e.g., sleepwalking and sleep-related eating, which are most common with the short-acting agents). As a result, they have been associated with an increase in motor-vehicle accidents41 and, in the elderly, falls (albeit inconsistently)42 and fractures. Recent longitudinal research suggests an association of long-term use of benzodiazepines with Alzheimer’s disease,43 but interpretation of these results is complicated by the possibility of confounding by indication, because anxiety and insomnia may be early manifestations of this disorder. Abuse of these agents is uncommon among persons with insomnia,44 but they should not be prescribed to persons with a history of substance or alcohol dependence or abuse.

Regular reassessment of the benefits and risks of benzodiazepine-receptor agonists is recommended. If discontinuation is indicated, gradual, supervised tapering (e.g., by 25% of the original dose every 2 weeks), in combination with CBT for insomnia, is strongly recommended for chronic users. Roughly one third of patients who used these discontinuation methods had resumed benzodiazepine use by 2 years of follow-up.45

Sedating Antidepressants

The use of sedating antidepressants to treat insomnia takes advantage of the antihistaminergic, anticholinergic, and serotonergic and adrenergic antagonistic activity of these agents. At the low doses commonly used for insomnia, most have little antidepressant or anxiolytic effect. Although data from controlled trials to support its use in insomnia are limited, trazodone is used as a hypnotic agent by roughly 1% of U.S. adults,35 generally at doses of 25 to 100 mg. Its side effects include morning sedation, orthostatic hypotension (at higher doses), and (in rare cases) priapism. Doxepin, a tricyclic antidepressant, is FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia at doses of 3 to 6 mg. It has shown significant effects on sleep maintenance (time awake after sleep onset and total sleep time) but no significant benefit for sleep-onset latency beyond 2 days of treatment.46 Few side effects were observed at these doses. Mirtazapine has antidepressant and anxiolytic efficacy at doses used for insomnia and is a reasonable first option if patients have insomnia coexisting with those disorders, but it may cause substantial weight gain.

Other Agents

The orexin antagonist suvorexant, which was approved by the FDA in 2014 for the treatment of insomnia, showed decreased time to sleep onset, decreased time awake after sleep onset, and increased total sleep time in short-term randomized trials.47 At higher doses (30 to 40 mg, which were not approved by the FDA owing to a 10% rate of daytime sedation), suvorexant showed persistent efficacy for these measures after 1 year of nightly use48; lower doses have not been studied for more than 12 weeks. Its major side effect at lower doses is morning sleepiness (5% of patients).

Ramelteon is a melatonin-receptor agonist that is FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia. Short-term studies as well as a controlled 6-month trial showed small-to-moderate benefits for time to sleep onset but no significant improvement in total sleep time or time awake after sleep onset.49 Side effects were limited to rare next-day sedation. A meta-analysis of trials of melatonin for insomnia (at a wide range of doses and in immediate-release and controlled-release forms) showed small benefits for time to sleep onset and total sleep time.50 However, the quality control of over-the-counter melatonin products is unclear.

Although controlled clinical trials to support its use are lacking, gabapentin is occasionally used for insomnia, predominantly in patients who have had an inadequate response to other agents, who have a contraindication to benzodiazepine-receptor agonists (e.g., a history of drug or alcohol abuse), or who have neuropathic pain or the restless legs syndrome. Potential side effects include daytime sedation, weight gain, and dizziness.

Areas of Uncertainty

Insomnia is an independent risk factor for depression, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. Controlled studies are needed to determine whether long-term treatment of insomnia with CBT or medications (or both) can reduce the risk of these disorders.

Both sleeplessness and the pharmacologic therapies used to treat insomnia are associated with complications. In those who do not choose CBT or do not have a response to it, long-term randomized trials comparing benzodiazepine-receptor agonists, sedating antidepressants, and the orexin antagonist suvorexant to inform the choice of medications are lacking.

Guidelines

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine25 and the National Institutes of Health51 have published guidelines for the diagnosis and management of insomnia. The recommendations in this article are generally consistent with those guidelines.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The woman in the vignette has a long history of insomnia, now complicated by nocturia and pain. Recently, owing to her physician’s concerns about her benzodiazepine use, she was switched to a low dose of trazodone, but she reports frequent and prolonged awakenings. Attempting to discontinue lorazepam and replacing it with trazodone were reasonable, given the amnestic and psychomotor side effects of benzodiazepines, although data from studies that directly compare these agents are limited. I would strongly recommend a trial of CBT, including (but not limited to) educating her that 7 hours is an adequate amount of sleep, reducing the time from bedtime to final awakening to that amount, and advising her to get in bed only when sleepy and to get out of bed when not sleeping. Over time, these approaches should reduce the duration of nocturnal awakenings, although she should be cautioned initially about an increase in daytime sleepiness. Attention to her nocturia and nocturnal pain will further minimize her nocturnal awakenings and their duration. If these approaches are ineffective, I would consider an increase in the trazodone dose (if this does not cause unacceptable side effects) or a return to lorazepam, informing her of (and regularly reassessing) benefits and potential risks."

Source: John W. Winkelman, M.D., Ph.D. in NEJM from 2 months ago

_________________

| Humidifier: S9™ Series H5i™ Heated Humidifier with Climate Control |

| Additional Comments: S9 Autoset machine; Ruby chinstrap under the mask straps; ResScan 5.6 |

Last edited by avi123 on Sun Oct 18, 2015 6:15 pm, edited 4 times in total.

Re: sleep aids

I do take .3mg of melatonin (300mcg) while I'm getting ready for bed. However, I also try to optimize other sleep factors related to sleep hygene, etc. I find that I'm more relaxed when I get to bed since using the f.lux app on my computer to filter out a lot of the blue light, for example. Using the computer is one of the last things that I do before going to bed, usually. Ear plugs also help me to not hear sounds other than my own breathing, which is kind of soothing.

I'm a very light sleeper, and if I change something in my routine, it can take me longer to get to sleep. For example, I tried a Pad-a-Cheek barrel cozy on my Swift FX mask the other night for the extra padding, and it took me a long time to get to sleep due to the fact that I felt a lot less leak control, and had trouble keeping the initial leaks down with it. An important thing for me in getting to sleep is to start the night with no leaks and their associated noises. Once I'm asleep, leaks will still wake me up, but it's easier to get back to sleep.

I agree that going to the prescribed sleep aids or a lot of over-the-counter sleeps aids should be your last resort. One should try to work on this without drugs first. For example, I doubt that melatonin will do you much good if you don't have decent sleep hygene habits.

I'm a very light sleeper, and if I change something in my routine, it can take me longer to get to sleep. For example, I tried a Pad-a-Cheek barrel cozy on my Swift FX mask the other night for the extra padding, and it took me a long time to get to sleep due to the fact that I felt a lot less leak control, and had trouble keeping the initial leaks down with it. An important thing for me in getting to sleep is to start the night with no leaks and their associated noises. Once I'm asleep, leaks will still wake me up, but it's easier to get back to sleep.

I agree that going to the prescribed sleep aids or a lot of over-the-counter sleeps aids should be your last resort. One should try to work on this without drugs first. For example, I doubt that melatonin will do you much good if you don't have decent sleep hygene habits.

_________________

| Machine: ResMed AirSense™ 10 AutoSet™ CPAP Machine with HumidAir™ Heated Humidifier |

| Mask: ResMed AirFit N30 Nasal CPAP Mask with Headgear |

Re: sleep aids

The best sleep aids will extend your total sleep time by about 30 minutes over using nothing. Basically, they don't work (for most people most of the time).

Improving your sleep hygiene is the way to go, at least at first. Don't go to bed until you're very tired, so that you associate masking up with falling asleep. Some folks advise wearing your mask while reading and watching TV to get used to it, but it sounds like you're past that stage. I only put my mask on when I'm ready to sleep and I'm usually out within 10 minutes. CPAP is like a cue for my brain to shutdown.

If you've been lying in bed for 20 minutes without falling asleep, get up and do something relaxing for 20 minutes. Then try again and repeat if necessary. Lying awake in bed just trains your brain to be awake in that situation.

Improving your sleep hygiene is the way to go, at least at first. Don't go to bed until you're very tired, so that you associate masking up with falling asleep. Some folks advise wearing your mask while reading and watching TV to get used to it, but it sounds like you're past that stage. I only put my mask on when I'm ready to sleep and I'm usually out within 10 minutes. CPAP is like a cue for my brain to shutdown.

If you've been lying in bed for 20 minutes without falling asleep, get up and do something relaxing for 20 minutes. Then try again and repeat if necessary. Lying awake in bed just trains your brain to be awake in that situation.

_________________

| Mask: AirFit™ P10 Nasal Pillow CPAP Mask with Headgear |

| Humidifier: S9™ Series H5i™ Heated Humidifier with Climate Control |

Re: sleep aids

One again, professionals don't seem to understand that the number of hours slept is irrelevant as it is the quality of sleep that is important. For this particular woman, maybe 7 hour is adequate but that can't be assumed as each person is different.avi123 wrote: Conclusions and Recommendations

The woman in the vignette has a long history of insomnia, now complicated by nocturia and pain. Recently, owing to her physician’s concerns about her benzodiazepine use, she was switched to a low dose of trazodone, but she reports frequent and prolonged awakenings. Attempting to discontinue lorazepam and replacing it with trazodone were reasonable, given the amnestic and psychomotor side effects of benzodiazepines, although data from studies that directly compare these agents are limited. I would strongly recommend a trial of CBT, including (but not limited to) educating her that 7 hours is an adequate amount of sleep, reducing the time from bedtime to final awakening to that amount, and advising her to get in bed only when sleepy and to get out of bed when not sleeping. Over time, these approaches should reduce the duration of nocturnal awakenings, although she should be cautioned initially about an increase in daytime sleepiness. Attention to her nocturia and nocturnal pain will further minimize her nocturnal awakenings and their duration. If these approaches are ineffective, I would consider an increase in the trazodone dose (if this does not cause unacceptable side effects) or a return to lorazepam, informing her of (and regularly reassessing) benefits and potential risks."

Personally, if I was sleeping well on a benzo, I would continue with the med and find other ways to guard against dementia. One can also get the condition not sleeping so as always, it is an issue of weighing the risks against the benefits.

49er

_________________

| Mask: SleepWeaver Elan™ Soft Cloth Nasal CPAP Mask - Starter Kit |

| Humidifier: S9™ Series H5i™ Heated Humidifier with Climate Control |

| Additional Comments: Use SleepyHead |

Re: sleep aids

Of course, you know more and are smarter than John W. Winkelman, M.D., Ph.D., we all know it.49er wrote:avi123 wrote:

One again, professionals don't seem to understand that the number of hours slept is irrelevant as it is the quality of sleep that is important. For this particular woman, maybe 7 hour is adequate but that can't be assumed as each person is different.

Personally, if I was sleeping well on a benzo, I would continue with the med and find other ways to guard against dementia. One can also get the condition not sleeping so as always, it is an issue of weighing the risks against the benefits.

49er

_________________

| Humidifier: S9™ Series H5i™ Heated Humidifier with Climate Control |

| Additional Comments: S9 Autoset machine; Ruby chinstrap under the mask straps; ResScan 5.6 |

see my recent set-up and Statistics:

http://i.imgur.com/TewT8G9.png

see my recent ResScan treatment results:

http://i.imgur.com/3oia0EY.png

http://i.imgur.com/QEjvlVY.png

http://i.imgur.com/TewT8G9.png

see my recent ResScan treatment results:

http://i.imgur.com/3oia0EY.png

http://i.imgur.com/QEjvlVY.png

Re: sleep aids

Avi,avi123 wrote:Of course, you know more and are smarter than John W. Winkelman, M.D., Ph.D., we all know it.49er wrote:avi123 wrote:

One again, professionals don't seem to understand that the number of hours slept is irrelevant as it is the quality of sleep that is important. For this particular woman, maybe 7 hour is adequate but that can't be assumed as each person is different.

Personally, if I was sleeping well on a benzo, I would continue with the med and find other ways to guard against dementia. One can also get the condition not sleeping so as always, it is an issue of weighing the risks against the benefits.

49er

Barry Krakow has said it is the quality of sleep that is more relevant than the number of hours.

Yeah, doctors are smarter than me but they are not always right just because they have the almighty MD by their name. Many people on this board who spent many years getting blown off by their MDs when they complained about sleep apnea issues are living proof of that.

49er

_________________

| Mask: SleepWeaver Elan™ Soft Cloth Nasal CPAP Mask - Starter Kit |

| Humidifier: S9™ Series H5i™ Heated Humidifier with Climate Control |

| Additional Comments: Use SleepyHead |

Re: sleep aids

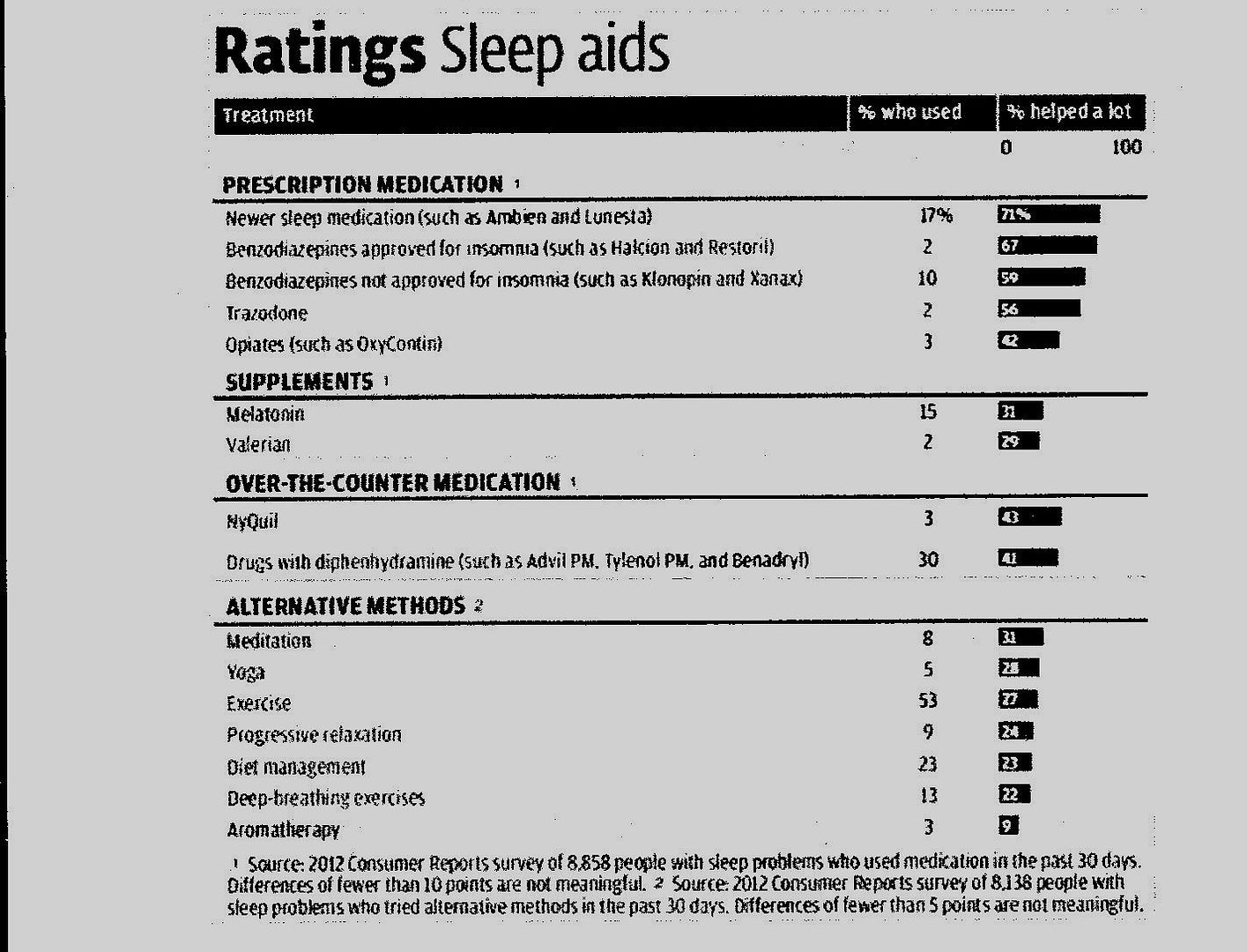

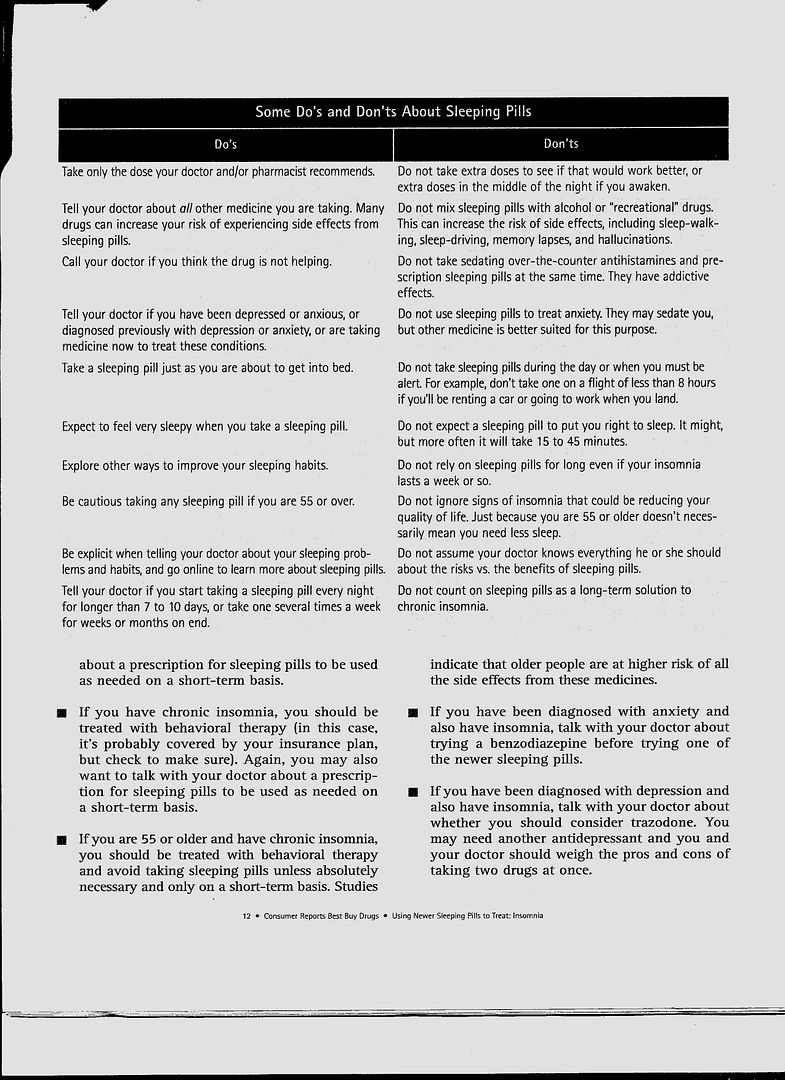

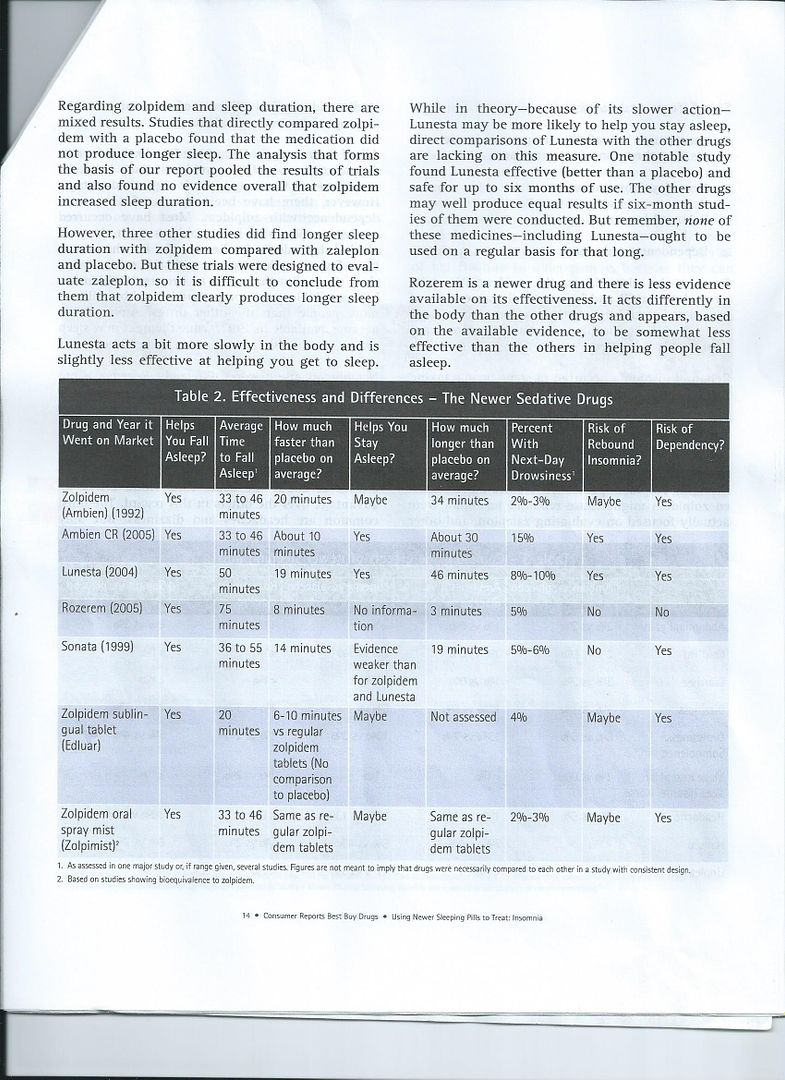

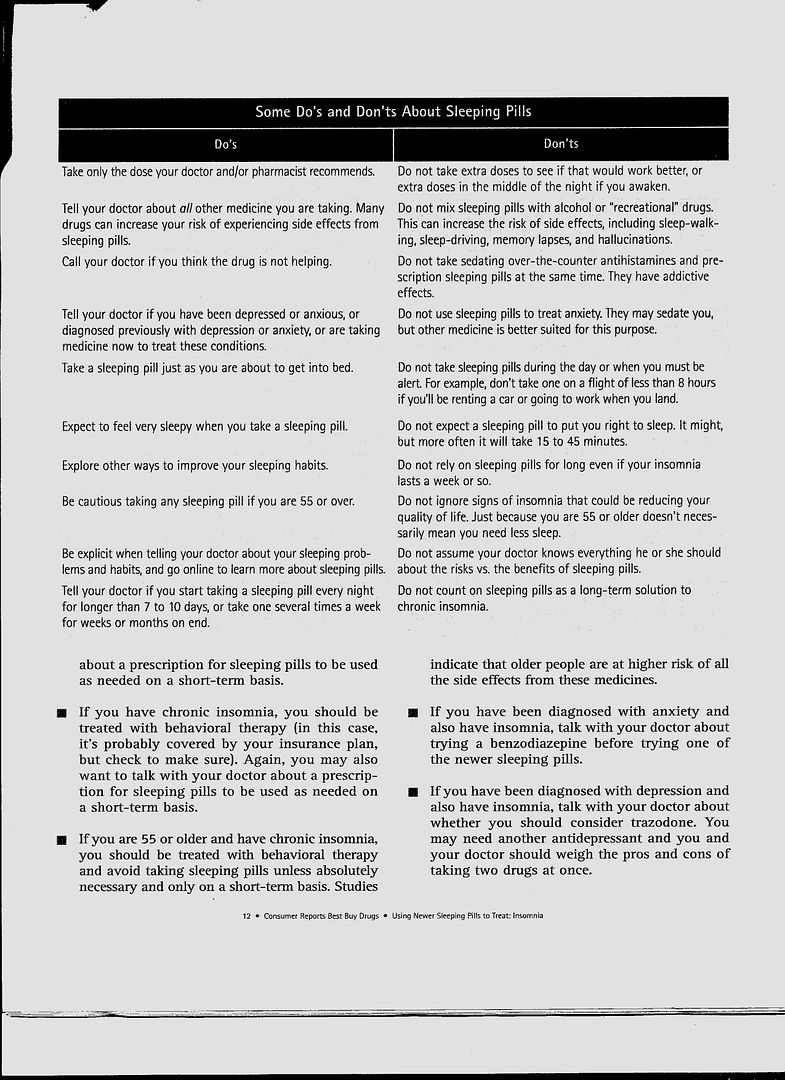

Sleeping pills for insomnia: Which ones work best?

Consumer Reports Best Buy Drugs compares the effectiveness, safety, and price of the most common insomnia medications

Published: May 2014

"For the average person needing short-term help for insomnia, we have chosen only one drug—zolpidem—as a Best Buy. Zolpidem is the generic version of brand-name Ambien. The generic contains the same active ingredient as the brand-name drug and is much less expensive. At a cost of $16 to $17 for seven pills, depending on dose and strength, zolpidem is less expensive than the other brand-name sleeping pills as well. { my Medicare BCBS insurance for prescription pays only for 15 Zolpidem pills a month. So I need to pay from my pockets about a dollar a pill for more pills}

Our choice of zolpidem is based not just on this price advantage, but also because the evidence shows it helps people fall asleep and stay asleep, and next day drowsiness is unusual (see the effectiveness table below). Thus, if you are getting a first-time prescription for one of the new sleeping pills, or if you have been taking one, we urge you to talk with your doctor about trying generic zolpidem.

The other forms of zolpidem—sustained-release (Ambien CR), dissolvable tablet (Edluar), and the oral mist spray (Zolpimist)—are more expensive and offer little if any advantage to make the higher cost worth it."

Consumer Reports Best Buy Drugs compares the effectiveness, safety, and price of the most common insomnia medications

Published: May 2014

"For the average person needing short-term help for insomnia, we have chosen only one drug—zolpidem—as a Best Buy. Zolpidem is the generic version of brand-name Ambien. The generic contains the same active ingredient as the brand-name drug and is much less expensive. At a cost of $16 to $17 for seven pills, depending on dose and strength, zolpidem is less expensive than the other brand-name sleeping pills as well. { my Medicare BCBS insurance for prescription pays only for 15 Zolpidem pills a month. So I need to pay from my pockets about a dollar a pill for more pills}

Our choice of zolpidem is based not just on this price advantage, but also because the evidence shows it helps people fall asleep and stay asleep, and next day drowsiness is unusual (see the effectiveness table below). Thus, if you are getting a first-time prescription for one of the new sleeping pills, or if you have been taking one, we urge you to talk with your doctor about trying generic zolpidem.

The other forms of zolpidem—sustained-release (Ambien CR), dissolvable tablet (Edluar), and the oral mist spray (Zolpimist)—are more expensive and offer little if any advantage to make the higher cost worth it."

_________________

| Humidifier: S9™ Series H5i™ Heated Humidifier with Climate Control |

| Additional Comments: S9 Autoset machine; Ruby chinstrap under the mask straps; ResScan 5.6 |

Last edited by avi123 on Sun Oct 18, 2015 6:01 pm, edited 1 time in total.

Re: sleep aids

Steve, during the week I watch TV from 11 PM till 1 AM. How else could I watch Charlie Rose show on the public channel from midnight till 1 AM ? That damn BBC News grabs the time slot from 11:30 PM till midnight. Then I take 10 mg of Zolpidem, put on the CPAP mask and fall a sleep till 7:30 to 8 AM. I have been retired since 1969.SteveGold wrote:The best sleep aids will extend your total sleep time by about 30 minutes over using nothing. Basically, they don't work (for most people most of the time).

Improving your sleep hygiene is the way to go, at least at first. Don't go to bed until you're very tired, so that you associate masking up with falling asleep. Some folks advise wearing your mask while reading and watching TV to get used to it, but it sounds like you're past that stage. I only put my mask on when I'm ready to sleep and I'm usually out within 10 minutes. CPAP is like a cue for my brain to shutdown.

If you've been lying in bed for 20 minutes without falling asleep, get up and do something relaxing for 20 minutes. Then try again and repeat if necessary. Lying awake in bed just trains your brain to be awake in that situation.

_________________

| Humidifier: S9™ Series H5i™ Heated Humidifier with Climate Control |

| Additional Comments: S9 Autoset machine; Ruby chinstrap under the mask straps; ResScan 5.6 |